Finding Your Voice

How can I fix the voice?

Advice for budding writers can sometimes feel like an endless loop of popular catchphrases: “show, don’t tell,” “avoid cliché,” and “write what you know” are touted as rules to live by, but such soundbites are often a too broad and vague to really be helpful.

A maxim whose meaning alluded me until very recently was that writers need to “find their voice” before they can produce anything of real merit. It wasn’t that I didn’t have a voice until recently, or that I didn’t know a good literary voice when I encountered one.

What I didn’t understand is the relationship between “voice” and writer’s identity – not just their literary identity, but their identity in the most personal sense. Because of that I didn’t quite know how to recognize my voice, or how to think about developing it.

My epiphany came with the help of novelist and essayist Zadie Smith – one of my absolute favorite writers-about-writing. Several months ago I was perusing a few essays in which Smith talks about “style.”

Photo Credit: David Shankbone

In “Fail Better” (which I recommend you read in its entirety), she writes:

[Certain critics] understood style precisely as an expression of personality, in its widest sense. A writer's personality is his manner of being in the world: his writing style is the unavoidable trace of that manner. When you understand style in these terms, you don't think of it as merely a matter of fanciful syntax, or as the flamboyant icing atop a plain literary cake, nor as the uncontrollable result of some mysterious velocity coiled within language itself. Rather, you see style as a personal necessity, as the only possible expression of a particular human consciousness. Style is a writer's way of telling the truth.

When I read this, a light bulb went off: we, as individual writers, write in our specific ways because we each have our own way of looking at and processing the world. The stylistic choices we make, even if they aren’t fully conscious, are anything but arbitrary – they are the outward manifestation of how the insides of our brains work.

Our “style” is how we externalize our individual inner landscapes using the tools of written language – what results from this fusion of identity and technique is a writer’s literary “voice.”

Say two writers meet for lunch at a café, and a young couple is having a fight at the adjoining table. Later each writer goes home and writes a scene based on what they saw.

They will probably attribute different emotional motivations to the characters, remember and report different details, and use language that is tailored to the point they’re each trying to make.

One writer’s description of the two lovers might be dramatic and tragic; the other’s might read as ironic, cynical, or darkly comic. These choices, and the two different pieces of writing that result from observing the same events, reflect the voices of two people who see the world very differently.

If you understand your voice as an organic outgrowth of your way of seeing and thinking, you’ll start to free yourself from preconceived ideas about how you think you should write.

Now I’m going to quote Zadie Smith again, this time her essay “This is How it Feels to Be Me.” She writes:

We cannot be all the writers all the time. We can only be who we are. Which leads me to my second point: writers do not write what they want, they write what they can. When I was 21 I wanted to write like Kafka. But, unfortunately for me, I wrote like a script editor for The Simpsons who'd briefly joined a religious cult and then discovered Foucault. Such is life.

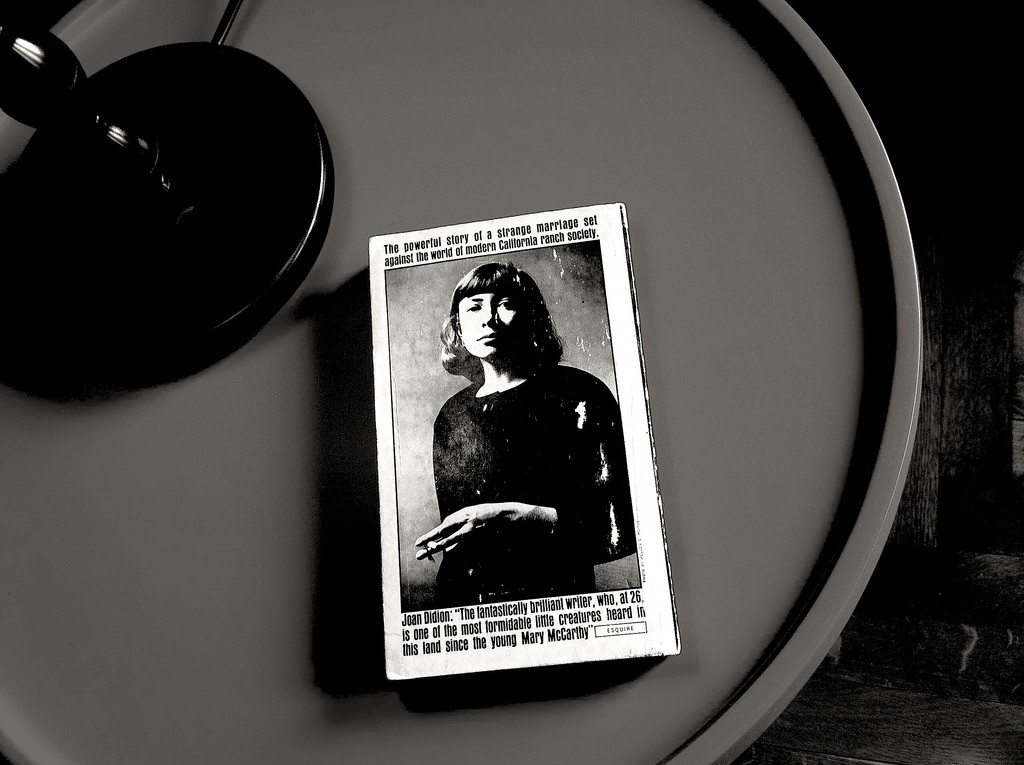

When I read this essay I had second “eureka!” moment. I too have had literary idols whom I desperately wished to emulate. For much of my 20s my personal Holy Grail was the famous essayist Joan Didion. I thought that if I could write like Joan, I’d have it all figured out.

Didion, the Holy Grail for many writers. Photo Credit: Incase

This, however, is a trap, and reading Zadie Smith made me realize exactly why. I can’t write like Joan Didion because I don’t live in Joan Didion’s head. I don’t see the world through her eyes, I don’t have her emotional tendencies, and I don’t react to things the way she does.

My attempts to write like Joan Didion always felt forced and ineffective -- not because I wasn’t good enough, but because I wasn’t Joan Didion. I’m still not, in case you were wondering.

You, my reader, may desperately want to write like William Faulkner, but unless you can take his brain and put it inside your own skull, your attempts to do so likely won’t turn out very well. That’s fine. You’re you.

So stop thinking about what William Faulkner might say about XYZ and start paying attention to what you have to say about it – not what you think you should say in order to sound smart and literary, but what thoughts and emotions actually rise up within you. Then write those things down without worrying too much about how you’re writing. This is one way to begin to identify your voice. Then you can refine this voice into a writing style that will express your ideas to an audience in the most artful and precise way possible.

Of course this latter “refining” part requires a lot of very focused work on craft. Practice, and revision, and the help of teachers and editors will come into play. But once you start to identify what it is you’re trying to express, this work becomes a much more focused and directional process.

You’ll develop a much sharper instinct for when your writing “feels right,” and when something isn’t quite coming together.

Keep in mind that our ways of looking at the world evolve over our lives, so our voices may likewise evolve over the course of our careers. But if you get into the habit of paying attention to the inside of your own head, and develop the tools needed to externalize that clearly, your voice will become something that you’ll never lose.